Rethinking Congestion

Early last week, I was riding my bike back to the South End of Burlington from the Downtown City Market at lunch time. With the mid-day lunch trips and construction detours, I immediately hit a long crawl of traffic on College Street where it crossed Church, and so I turned off to cross Church Street via Bank before turning to make my way south on Pine. While it was only a few minutes out of my day, the minor disruption in my usual movement habits had me reflecting on the experience, and there were three things that stuck out to me.

First, was how easy it was for me to navigate around the congestion on a bike compared to the vehicles that were stuck in it. Once I saw that the Church Street crossing on College was going to take several minutes of waiting to get through, I was able to dismount my bike, walk to the sidewalk, and then take a detour on Center Street to Bank Street. I probably got home before the car in front of me on College even made it through the intersection. Drivers, however, were trapped both by the other cars around them, and by their physical inability to make a tight maneuver like that in the first place. Even though we both used the road in a similar way, our ability to adapt to the emergent environment was considerably different.

The second thing I noticed was how clear it was in that moment that the congestion wasn't created by the construction detour, or by the pedestrians crossing on Church Street, but by the cars themselves. Yes, the road closures on Main Street pushed more traffic into less space, but it was the nature of the cars that created the congestion. It was the size of the vehicles, their inability to maneuver, and the need for them to completely stop to let pedestrian traffic cross that combined to form the gridlock. None of these limitations applied to me on a bike, which is why I was able to easily avoid the whole situation.

The final thing that stuck with me, though, was the tension in the air. As anyone who gets around the city by walking or biking can attest to, you quickly learn to read the "body language" of vehicles out of a need to keep yourself safe. In this moment of congestion, I could feel the frustration of the drivers trapped in it. Usually, I'm focused on what that means for me: I need to stay alert and keep my distance, because annoyed drivers are more likely to make sudden, erratic, and dangerous movements. But after I got home, I found myself thinking about what that frustration felt like from their perspective. What did they see as the problem? What solutions were they dreaming about as they stared at the bumper stickers on the car in front of them?

As I put myself in their shoes—and as I remembered how I personally used to think about these things when I owned and drove a car—I realized that there was most likely a significant gap between the average person's understanding of the causes of traffic congestion and its solutions, and the actual underlying system dynamics that govern it. This is worrying, because in many cases those underlying system dynamics behave in a counter-intuitive way. Without careful consideration, attempting to act on our collective intuition can make the situation worse. It struck me that this may be why our transportation network doesn't seem to be meaningfully improving.

This reflection, and the way it bridged my perspective with others, felt like the perfect narrative starting point for Turning Lane to begin laying the groundwork for a systems-centered understanding of our transportation network here in Burlington.

So, let's dive into it.

Seeing the System

The fundamental reason that our intuition breaks from reality when it comes to system dynamics is that we see the world from our own individual perspective, and at a specific point in time. In the case of traffic congestion, we imagine how different things would be if everyone "knew how to drive" like we do. When it's finally our turn to cross Church Street, we don't see any pedestrians delaying our crossing as "our fault". We see each individual part of the system only as it relates to us, and then construct a story about it with our selves at the center. We know the "right" behavior that would avoid issue, but we don't acknowledge that oftentimes, the system around us makes our decisions for us.

The issue with this intuitive approach is that it is rooted in seeing the problem from an individual responsibility lens, when the issue lies at the system scale. When you take a step back, the story of how you as an individual play into the system is irrelevant. Sometimes you might get lucky and be the person who gets through the intersection the fastest. Other times you might get unlucky and be the slowest. But if you cross an intersection enough times in your life, you'll eventually play all of those roles and average out to the median. And so when we ignore the system dynamics, we ultimately just pass the problem on to future versions of ourselves.

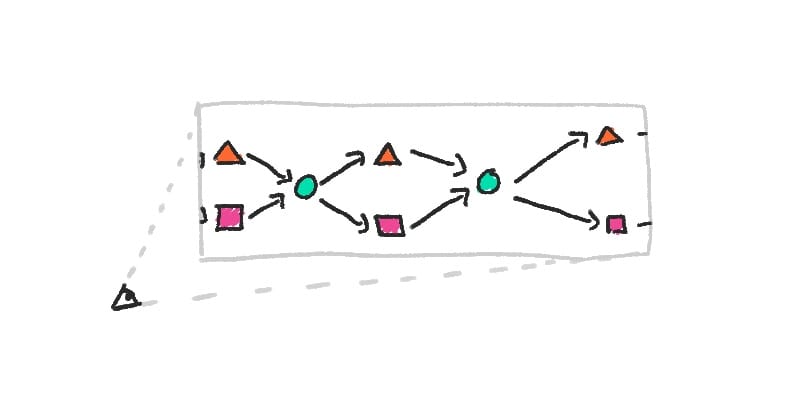

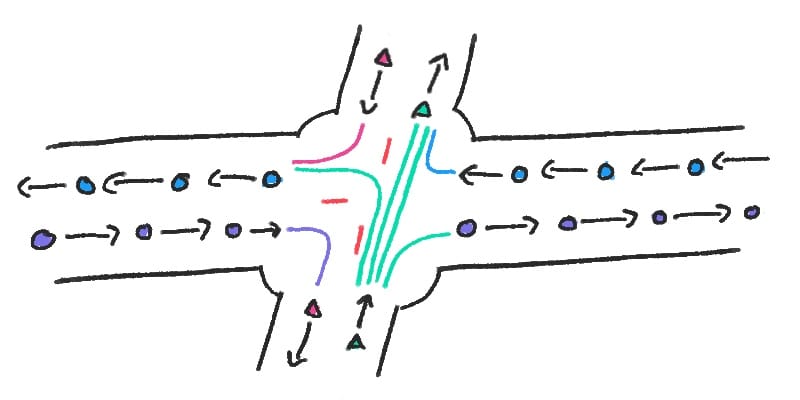

But what does it look like to see this problem at the "whole system" level? When it comes to traffic, it looks like this: There are some number of people moving along a route in one direction, and some number of people moving on a different route in another direction. When those two routes intersect, we end up with two streams of movement that want to occupy the same space in the intersection.

Naturally, two vehicles can't occupy the same part of the intersection at the same time. This means those intersections must be negotiated between the two streams of movement, and this negotiation takes time. The less space there is in the intersection and the more potential paths that cross, the more time the negotiation takes.

When we add the human angle back to the equation, we get even more delay. Unlike the "autopilot" street design of highways and suburban arterials, urban streets require a significant amount of dedicated attention to navigate due to the diversity of street life. There are people walking, confused drivers from out of town, parents transporting their children on long-tail cargo bikes, and events in the park. The attention required of drivers to navigate this diversity ultimately results in even longer wait times at intersections.

These two elements—the physical limitations of moving through a shared space, and the attention required to navigate a dynamic urban environment—are what results in slower overall vehicle speeds and the traffic congestion we see in Downtown Burlington.

Solving the System

So what can be done to reduce congestion downtown?

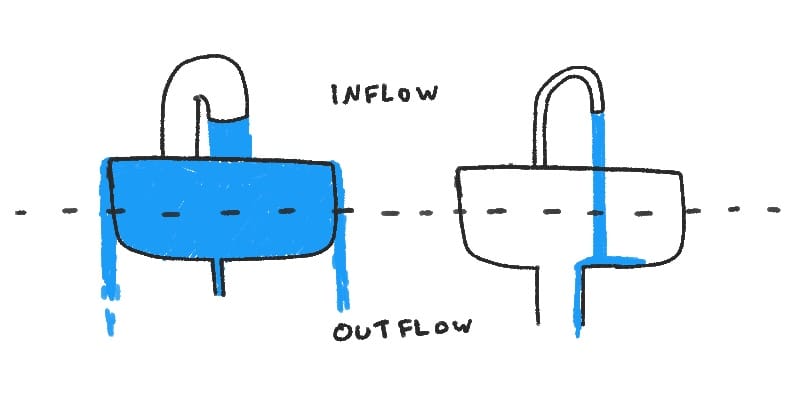

From a system analysis perspective, here's what this congestion boils down to: the "outflow" (i.e. the rate at which cars are moving through the intersection) is less than the "inflow" (i.e. the rate at which cars are approaching the intersection). There are more cars arriving at the intersection than there are crossing in a given slice of time. When you have a system with more coming in than going out, you get a buildup.

You can think about the intersection like a sink with a wide faucet, but a narrow drain. It's going to fill up with water—in our case, traffic—and eventually overflow. This gives us a clear set of goals to pursue to try to reduce the traffic congestion: we can either increase the outflow, or decrease the inflow.

Increasing the Outflow

The intuitive solution that most people jump to is to speed up travel speeds through the intersection. In fact, in most places touched by modern traffic engineering, this is exactly the solution on display. Wide roads allow for higher speeds and push cyclists and pedestrians to wait at the margins, while dedicated turning lanes and fine-tuned signal timing maximize the amount of vehicles that can move per phase without conflict. This makes sense based on the pure physics of it all: making an intersection physically bigger and separated by time means less of it needs to be negotiated.

However, there's a really important tradeoff with this design: it's not a great experience to be outside of a vehicle in these places. When more cars are moving faster through an area, it becomes louder and more uncomfortable to be around, and more dangerous to share the street when walking or biking. This makes these areas less desirable to stroll through and shop in, to dine outdoors, or even just to live. We trade vibrancy for convenience. What's the point in making it faster to get to a worse place?

Aside from the way these changes negatively impact the quality of places, we also quickly run into physical limitations when trying to increase the vehicle throughput at an intersection. As we already discussed, speeding up vehicles through intersections requires more space. In the suburbs, where destinations are spread out and public right-of-ways are very wide, this additional space is often easy to claim—though the quality of those places still suffers for it.

But in urban places, the existing built environment often means we don't have that luxury of space. For example, another long-time problem intersection in Burlington is Pine and Maple Street, which backs up quite a bit during daily peak travel times—even without construction. But because that intersection is constrained by an urban building pattern where homes are built right up to the sidewalk, you'd need to demolish homes to increase the size of the intersection and its vehicle throughput.

And so, if increasing intersection throughput in urban places makes them more uncomfortable to be in outside of a vehicle, reduces the desirability of those destinations in general, and often would require buying land and demolishing homes to achieve, it leads to a general conclusion that will be true in most cases: while operational tweaks can eke out some minor efficiency gains, substantially increasing the vehicle throughput of intersections in built-out urban spaces is a dead end.

Decreasing the Inflow

This leaves us with the less intuitive option: if we can't meaningfully increase the outflow of vehicles getting through an intersection in an urban environment, then we have to decrease the inflow of vehicles coming into it. This would result in a system dynamic where a vehicle can get through the intersection faster than a new one arrives, keeping the intersection clear and eliminating the issue of congestion.

There's a catch, though. The reason this option is counter-intuitive to explore is because we can feel a tension underlying the concept. How could it be a good idea to reduce the amount of vehicles in an urban environment where there is a high demand for transportation? We can't just eliminate the demand for movement, especially in a place with many commercial and residential destinations. But through proper framing, the question answers itself: "How can we move the same amount of people through an intersection with fewer vehicles?"

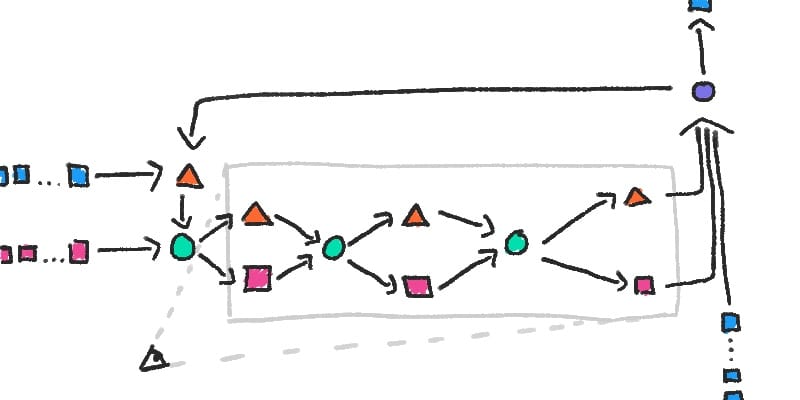

Vehicles as the Bottleneck

The answer, of course, is to have there be more people in each vehicle. The answer is mass transit. During times of peak congestion, a single bus in GMT's fleet can replace up to thirty cars, assuming a moderately full bus and somewhere between one and two passengers per car. When a single round of crossings at an urban four-way stop—like Pine and Maple—can take around fifteen seconds, each full bus through the intersection could eliminate up to seven minutes of time waiting for other vehicles moving in that direction. Instead of moving vehicles through the intersection faster, we just move more people per crossing; in the end, the math works out the same.

Scaling this up, this is exactly why highly functional cities rely on mass transit systems as the backbone of their transportation network. It's not just a nice thing that big cities can have because they have the money for it, and it's not just an "extra" way to get around for lower-income people who can't afford cars. It's because—from an engineering perspective—moving a lot of people in urban environments requires people moving capacity that far exceeds what personal vehicles can functionally deliver in limited space.

In cities that design mass transit systems well, it is also usually the fastest and most convenient way to get around for everyone, making it the preferred transportation mode for people of all backgrounds and incomes. There's a reason the New York City Subway is referred to as "the great equalizer": whether you're a fry cook or a Wall Street banker, the subway is usually going to be your most convenient option to get home from work. From the inverse angle, it explains why a city like Los Angeles is so notorious for its traffic jams: it's not the presence of too many cars, but the relative lack of mass transit options to alleviate congestion in the face of the tremendous transportation demand.

Eliminating the Intersection

When we untether our imagination of transportation networks from the "cars on roads" paradigm, we'll find that we can get more creative in how to solve for the intersection bottleneck. In fact, when looking at other transportation modes, we can often find ways to eliminate intersections altogether.

To minimize the impact of intersections on buses, bus signal priority systems can be used to track the locations of buses and adjust the traffic lights for approaching buses, either by extending a green light, or shortening a red.

When combined with dedicated bus lanes to avoid congestion that cars might still inflict on the network, these two components can dramatically reduce the travel time of buses along urban transit corridors within and between town centers. For example, with a future re-connected Saint Paul Street, bus signal priority systems, and a dedicated bus lane along Shelburne Road, an express bus could get from the Burlington Downtown Transit Center to Shelburne's Village Center in just over 10 minutes.

While not yet relevant in the Greater Burlington context, mixed traffic "light rail" systems—like trams and trolleys with tracks in the existing road—can use the same signal priority systems and dedicated lanes that buses can use to much the same effect, but with even higher passenger capacities. Meanwhile, "heavy rail" networks—like metros, commuter, and regional trains—tend to go a step further by pursuing full grade separation, meaning the tracks exist on a different plane from roads and sidewalks altogether.

As a result, these trains never cross paths with other people or vehicles at all, meaning they never have to slow down, and only ever stop moving at stations. Taken to the extreme, you end up with the subway tunnels and elevated rail lines that let trains move massive amounts of people very quickly and directly between destinations, even through some of the densest urban places on the planet like Manhattan and Tokyo.

Shrinking the "Vehicle"

Now that we're exploring alternatives to cars, we can actually go back and reassess ways to increase the outflow of an intersection. The limiting factor before was that we couldn't make the intersections bigger, because there wasn't the space to do so. But what if we made the "vehicles" smaller?

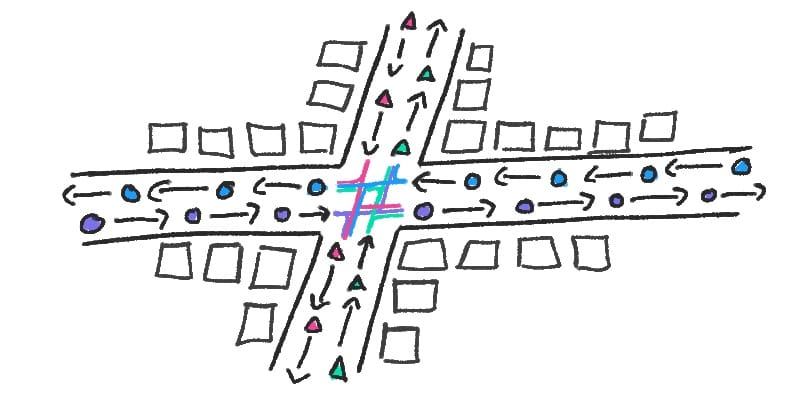

Enter the humble pedestrian. Outside of a vehicle, our collective spatial awareness allows crowds of people to move through each other in every direction all at once. This is a key characteristic that plays into the transportation network at the very end of a trip, at the "capillaries" of the system where people arrive and gather in urban places. While pedestrians don't move very fast, the sheer number of people that can move through a space at the same time on foot is far beyond what any other transportation mode can support. For places where a lot of people are not moving very far, like city centers and tourist destinations, nothing beats space designed for pedestrians. Obviously, the Church Street Marketplace is our most famous local example of this type of transportation infrastructure, and there's a reason it's well known as a vibrant and enjoyable place far beyond Chittenden County.

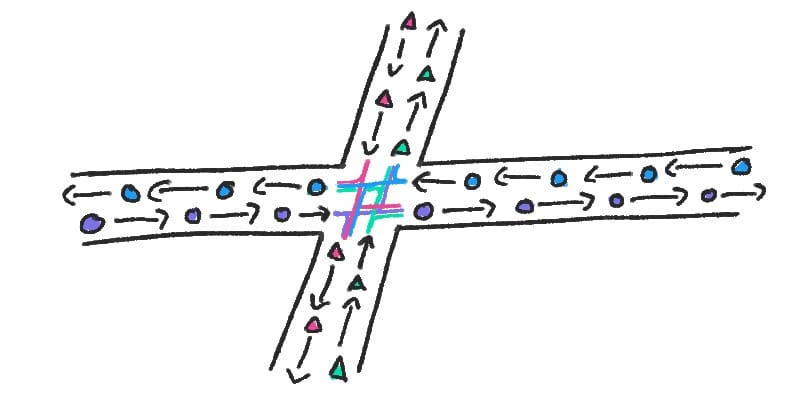

Finally, we have the bicycle. Although we have spent the past 50 years being asked to think of bikes as vehicles under the model of "vehicular cycling", people on bicycles are actually far more functionally similar to pedestrians than to cars. Bicycles and their riders exist in the human realm, are able to make eye contact with others, and have a similar mass to pedestrians, making them a minimal threat when traveling at average speeds. When bicycles can be completely separated from car traffic, they also tend not to require any signals to manage intersections, and cyclists can intuitively manage them without stopping—just like pedestrians.

While these cyclists are sharing a road with cars, notice how they all get a crossing signal at the same time yet manage to efficiently cross from multiple directions at once without issue.

At this point, a larger idea should hopefully be clear: the physical issue of navigating intersections—which is one of the key bottlenecks of urban transportation network throughput—is almost entirely an issue for cars. It's not an inherent problem for transportation systems in general, and arises out of both the space inefficiency of cars and their unique inability to efficiently negotiate intersections.

Other Bottlenecks

As a quick note for the sake of completeness, I'll point out that intersections are not the only interactions on the street that can create congestion. In reality, any situation where a vehicle is able to turn or change its speed has the ability to alter the flow of travel. Other prime examples are driveways—where vehicles are turning into and out of the road—and street parking—where vehicles will stop to pull in and out of parking spaces.

However, most of these other bottlenecks end up being very similar in shape to the issue of intersections, and their impact on the different modes of transportation is also largely the same. But it does highlight that our overuse of street parking and our historic development pattern that has resulted in so many driveways on major roads are also serious contributors to traffic congestion in the city.

The Local Angle

Let's bring it back to Burlington now. The ongoing road construction downtown has been framed as disruptive for two separate reasons. For businesses right along Main Street, the degraded streetscape makes it difficult to get to and uncomfortable to be in, which reduces a lot of the natural foot traffic. This is, unfortunately, a very difficult problem to avoid, but the silver lining is that the work being done will result in a significantly improved streetscape for decades to come. The people-oriented business environment of Main Street will be second only to Church Street once construction is complete.

However, the broader disruption—and the experience that prompted this article—has been how the construction has impacted the transportation network downtown. The public discourse has largely been focused on how the street and intersection closures have had significant detrimental impacts on the ability for people to drive through and park in the city. While this is obviously true, I want to connect the principles above to two other ideas that change the way I look at the transportation situation downtown.

Diversity Adapts

The first thing I want to call out is that the construction has predominantly impacted driving, not transportation as a whole. When walking through the city, it is easy to reroute through shifting detours. As evidenced by my opening story, it's also very easy to do the same while cycling. While buses are impacted by the increased road congestion, we should understand from our system exploration above that they are not the cause of that congestion, and if more car trips were shifted to walking, biking, and transit, then congestion would be reduced significantly.

The principle underlying these observations is that in a dynamic system, having a diverse set of options with a healthy amount of overlap—or redundancy—allows the system to adapt in real time to changing conditions. Or, as the saying goes: don't put all your eggs in one basket. Unfortunately, our transportation system does exactly that, and so what should be a minor disruption becomes a significant problem. Instead of the takeaway from this downtown construction saga being "We need to have more attention given to the needs of drivers to get around the city by car", it should be "We need to significantly increase the viability of other modes of transportation downtown". As it stands today, our transportation network is fragile because it is homogeneous.

This is What the Future Looks Like

The second thing I want to call out is that the congestion we're seeing from construction is a glimpse of what the future will look like in Burlington if we don't build out alternative transportation options starting today.

As we discovered earlier, the root cause of the congestion is not the construction itself, but the way it overloads intersection capacity downtown. Once the construction is finished, traffic will be able to re-balance across the road network and congestion will most likely be reduced to a more manageable level. But how long will that smooth traffic last in a growing city? To get an idea of what the future looks like, let's do some quick "napkin math" of Burlington's road network to get an idea of how its capacity changes over time.

Let's assume that, before construction, Burlington's road network could efficiently handle 1000 cars per hour (CPH) without getting congested, and that it was averaging about 900 CPH in real usage. Most of the time it functioned well, with occasional spikes during peak hours that pushed it above the comfortable 1000 CPH threshold. Now, during construction, the closures have diminished the capacity to 800 CPH. Because there are not enough viable alternatives to driving, the average CPH has remained largely the same, dipping to 850 CPH. This means that average conditions are beyond the network's capacity, pushing the system into dysfunction. Once construction is complete, we can expect the network capacity to go back up to 1000 CPH, and for smooth operation to return.

But again, the future is not static: there are thousands of new homes in the pipeline for the Burlington region over the next decade, with a significant number of those in and around Downtown. If we continue making much needed progress on the extremely acute housing shortage that we face, this trend will only accelerate. If we require that all of the new households that occupy those homes bring a car or two with them and use them for most trips, the 900 CPH demand baseline will rapidly increase. Eventually, that number will surpass the 1000 CPH maximum capacity of the road network, and the kind of congestion we see downtown right now will become permanent—and potentially worse. Unlike today, where we are relying on the reopening of closed roads to add capacity back to the system, there will not be any viable options to expand road capacity.

To be completely clear: to accommodate the economic development and housing growth that Burlington desperately needs, we need to immediately and rapidly build out high quality and overlapping active transportation and public transit networks because we do not have the physical space to meaningfully expand transportation capacity for cars within the city. The amount of people that want to live here, and the amount of business that we can—and should—support, requires more transportation than we can physically supply with cars as the dominant mode of transportation. And again, the only way to reduce the demand for driving and avoid overloading our transportation system is to provide viable alternatives to driving. This is not an ideological statement; it's a mathematical one.

What We Can Do

Getting into the details of exactly how we expand the capacity of our transportation system is the long term mission of Turning Lane. Every one of those changes—from specific design tweaks for crosswalks and bike lanes, to reclassifying every segment of our road network into heterogeneous use categories, to rethinking our regional planning processes—will require a lot more ink than a quick set of action items here. So instead, I want to focus on the really big picture things that need to happen, and which will carry through the action this newsletter calls for over time.

The overarching theme is this: we need to acknowledge that this project of rethinking urban mobility in the Burlington region is something that needs to happen, will require a lot of concerted effort, and that we are not currently doing this. Yes, there are a lot of conversations being had, there are plans in motion, and there is a lot of money being spent. But we are not having the right conversations, making useful plans, or spending money on things that matter. While this will also take many more future articles to elaborate on, the proof is in the pudding: there are more people are "driving alone" in Burlington today than there were 10 years ago. That's not the result of a concerted effort to rethink urban mobility, but hard evidence that we are moving in the wrong direction.

We can contrast this with the coordinated movement on our housing shortage. Over the past five years, the public narrative around housing has shifted considerably in Burlington, to the point where the majority of people understand how critical housing growth is to the future of the region. Major pro-housing zoning changes have been enacted locally, while three major housing bills have passed through Montpelier in as many years. There are now more people demanding new housing than there are people opposing it; not necessarily because we all individually need more housing ourselves—though that is the case for many—but because we have learned how lack of housing creates secondary impacts that affect us all.

This is the kind of public opinion shift that needs to happen around transportation. From my perspective, getting people on board with transportation reforms should be easier, because creating more high-quality transportation options would benefit almost everybody directly, including those who need to drive. However, this shift does face considerable practical and cultural headwinds. We've inherited a transportation system that effectively requires driving a car to get around, and while some people have been left behind with that requirement, most people have built their lives around it. None of us have directly contributed to creating this system, and all of us are doing our best to make it work for us. But it is absolutely possible to transition to a new transportation system without making life considerably harder for people who drive. There is a lot we can add to our transportation system without taking away options that people rely on.

Unfortunately, we're also in a uniquely weak position at this moment in time because of the larger political environment: federal funding is drying up, and lack of investment from the legislature is pushing GMT into crisis. Burlington itself is facing budgetary shortfalls that are narrowing our vision of how to invest in our future. Construction costs are rising. When it rains, it pours, as they say. But while we may be caught in the storm without an umbrella right now, that shouldn't mean that we lay down and give up.

Okay, But What Can We Do?

As a city, we need to be focused, we need to get creative, and most importantly, we need to want to build something better. There's a narrow path toward making this change in a rapid, equitable way, and it requires three main things.

First, this effort of rapidly building out safe, affordable, and convenient alternatives to driving needs the full support of city leaders and decision makers. Like tackling our housing shortage, this needs to be a bipartisan effort with active champions in the Mayor's office and the City Council. It also needs to be an explicit goal for city staff across all departments, but particularly in the Department of Public Works. I would argue that we may need a new, dedicated city office that doesn't currently exist to spearhead this effort, and realistically, this leadership alignment needs to be present not just in Burlington but in every city and town in Chittenden County's urban core—mobility doesn't end at municipal boundaries.

Second is that we need a new approach to transportation planning that is aggressive in its pursuit of building new transportation options that both expand the overall transportation capacity of the network, and explicitly shift as many car trips to alternative modes as possible. We need a planning process that is lightweight, capable of running experiments and making calculated bets, and able to adapt to new information on the fly. We do not need processes that are fragile, monolithic, and prescriptive. Critically, this new approach needs to focus on providing alternatives that are so good that people choose to drive less, and don't miss it.

Finally, we need to build an informed and vocal coalition of residents that demand these changes and hold our leaders accountable. We will probably need some of those people to run for office. Just like with housing, meaningful progress won't be made until it has the active, vocal support of residents who are ready to fight for change.

If you've read this far, this coalition may include you.

Let's get to work.

Thanks for reading. If this article gave you a new perspective, I hope you'll share it with a friend, family member, or colleague that you think might also find it interesting.

And if you have room in your inbox for an article like this a few times a month, I hope you'll consider subscribing, too.